WHAT HAPPENED YESTERDAY ON CLYDESIDE?

On a day when Gordon Brown has announced his resignation from Parliament and the Scotsman newspaper declared that nothing has really changed in Scottish politics; when yesterday in Finnieston you could walk from the X Factor-esque rally for Nicola Sturgeon at the Hydro to the assembled Trots and Ne'er -do-wells at the Radical Independence Conference in the Armadillo...and then pop into the Country Living Christmas Fair to pick up some lovely designer soaps at the Exhibition Centre, it might be as well to ponder what on earth just happened on the banks of the Clyde. Did the water turn Red? Was that glitter shooting out of the cannons at the end of Dougie MacLean's last chorus of "Caledonia" really gold?

Let's remember, first of all, that these were gatherings of losers. Over and over again at both events, on the platform and off, people talked about how they couldn't quite believe we were all here. But it does seem that the minute the votes were counted, something strange happened to both the No and Yes sides' campaigners as soon as things were "back to normal". The Old Normality turned out to be a consummation devoutly to be wished by one side and confidently denied on the other. The gulf between both sides, still, is as much a matter of temperament as logic and is as profound as ever. We seem to inhabit entirely different versions of reality and neither version of reality is particularly well defined.

The division now is between two versions of what "normal" might mean in Scottish politics today. The gulf between rival realities has deepened rather than disappearing since September. For the former No campaign, this refusal of their reality seems like inexplicable arrogance and posturing. While for the Yes side, the "new reality" has become an article of absolutely necessary faith. Belief and hope have become aims in themselves to set against the nullity and hopelessness of other peoples' "normal". If they look at each other at all, the two sides stare in bewildered mutual contempt. And before I get to what I think is going on with "Our" side, let me put it in the context first of the extraordinary consequences that winning the referendum has had for "Them."

(And me draw a preliminary line between those who voted No in good faith, in favour of the social and economic solidarity and stability of the UK and of the No Campaign Parties, in whom, unfortunately, those No voters have had no option but to put their faith as Trustees of that solidarity and security.)

First, as one might have expected, the No "alliance" immediately split into the war of each against each that passes for normal, political culture. At five minutes past ten on September 18th, the dominant UK branches of Better Together got back to being "grown-ups". Scotland was irrelevant again, and with relief Cameron and company got back into the serious business of who gets whose nose in the Westminster trough in the second half of May next year. Again, as one might have expected, the Tories were better at this, exposing the comparative lack of focus and purpose of UK Labour who have gone on to spectacularly fail to take any strategic advantage of the Tories' difficulties with UKIP. So far so titillating for the hacks and pundits whose own bored nihilism explains more than anything else the inane but energetic attraction of Nigel Farage. More seriously, it is the same lack of what an older generation of Britons called "bottom" and which Yeats might have called "conviction" that allows a retired second rate pop singer to run rings round the Leader of Her Majesty's Loyal Opposition in a discussion of taxation and has the "other ranks" of loyal Jocks in a bit of a pickle.

This is because, despite the Scotsman, Scotland has changed in the course of referendum campaign. The hope (and underlying anxiety) of both the events I attended yesterday on the banks of the Clyde is that this change is sustainable. The ineptitude and emptiness of British politics has been a tremendous help so far, of course, but what both events yesterday in Glasgow now signal is that the former "Yes" campaign understands that momentum of its own is required in order to keep a "movement" moving. And that we can't rely on the UK parties being dickish clowns forever.

It isn't rocket science. As Robin McAlpine pointed out most clearly in the strategic conversation at the RIC event, that our no longer having the simple question of Yes or No on a single identified future date leaves us with something of a vacuum around which to attempt to cohere. Normal politics, the stuff that politicians do, simply doesn't have the same focus or energising clarity. On the other hand, the nitty gritty of who is going to stand in what seat at the Westminster elections in May naturally brings with it rivalries and a clash of interests between the "Yes" parties...and at least part of what happened yesterday was the beginnings of a return to sectarian power display and posture taking on all sides.

There was danger as well as celebration in the air. Clearly, we can't rely on "keeping "it" going. We have toi redefine "it", and re-cohere around whatever "it" turns out to be.

THE ELEPHANT IN TWO ROOMS

There were other predictable points of contrast between the SNP and RIC events, of course. The RIC Conference was longer on content and shorter on triumph. The SNP rally was short on nuance and big on bombast. These were partly the differences between the size as well as the nature of the crowds in the respective venues. Another key difference was that while one event referred fairly frequently to the other, the other made no mention at all of the one. Bet you can't guess which way round that was.

However, both events were trying to seize on the same thing. Both were claiming custody of it, and both were struggling to define what "it" was. Because "it" was something that happened to us in August and September , something that felt like the engagement and empowerment that democracy is supposed to be. The SNP used music and lighting and numbers to attempt to embody and sustain that excitement, and to pretend, I think, that the 92000 membership they have now is the clearest demonstration that a defeated campaign is still going on and pretend that this movement can be easily and painlessly translated into their party political purposes. And if anyone makes a fuss about that it's their fault.

The RIC conference, more cerebrally, tried to get its collective head around both the problems of definition and the sustainability of an exciting new lease of life for the Scottish left. Both events succeeded, I think, in their own terms, in imitating the engagement we all felt in the latter stages of the campaign. Emotionally speaking, each event cemented a good deal of that feeling, and, after all, we only have six months to go until the next big political "event", and surely both the SNP and the wider movement can sustain a shared focus for six months? That was the question both events tried to answer, or rather, that one event pretended wasn't a question, and the other pretended was a much easier question to answer than it really is

Because that future has yet to be pinned down, let alone agreed on as an aim, let alone cohered around as a single strategy. Rather, a whole bunch of specific futures are gradually taking shape in different peoples' hearts and minds. Not just in terms of electoral strategy, the No side fragmented the moment the referendum vote was in. And it was clear to me yesterday that the assertion of togetherness of the Successor Yes Campaign yesterday in both arenas protested unity beyond credibility.. The very intensity of our with to "keep it together" demonstrated that we are beginning to fragment, or at least to fear fragmentation.

The vagueness of what we were voting Yes or No to was the defining characteristic of the campaign. That vagueness was the greatest weakness of the Yes campaign for those inclined to vote No and, at the same time, iit was the strongest glue for those who voted Yes.

On the one hand, we had the SNP acting as if the future was all about their success, their enormously enhanced membership, about their immediate strategy of "holding Westminster's feet to the fire."

Interestingly, they got much bigger cheers for the Red Lines of Principle they share with the wider movement, like no replacement for Trident and no deal with the Tories than they got for any engagement of any kind with the Smith Commission and its processes. The Party leadership know, of course, that a Party political view of reality is always partial, but we who are not Party leaders should not be remotely surprised at politicians acting like politicians.

On the other hand, over the way at the RIC, there was just the beginning of whining going on from the junior parties, the Greens and the SSP, that they were being crowded out of the first past the post scenarios being acted upon by Big Sister over the way. There was just the beginning of confusion between the emotionally satisfying impulse to take as many seats off Labour as is humanly possible in May and the need for the newly empowered allies in the Yes campaign to stake out their own territory.

In narrow terms, the most urgent task of the broader movement, and one that was being constantly addressed yesterday - though mostly still between the lines - was exactly whether or not, in this new National/Political territory of "Scotland the Changed", the temptation to retreat to the old, familiar political territoriality can be overcome. Can we find a replacement for the shared focus that the Yes/No question gave us? Can we come up with a form of words, some basic principles, around which we can unite as a movement that will sustain us through the next few years.

The elephant in both rooms was, of course, "the Yes Alliance." and what now seems to be the certainty that what carried us into September 18th as one movement is not going to do the same at the Westminster elections. The urge to recrimination about this was palpable if largely unexpressed among the RIC delegates, and also, interestingly, lurked below the apparently triumphalist surface of the SNP event. From the perspective of the SNP juggernaut, the smaller parties might all too soon become irritants and not allies. After all, those Labour MPs are not sitting on small majorities in our cities, they are sitting on whopping great big ones. It may seem like long ago in a country far, far away, but Labour did extremely well in Scotland in the general election of 2010 and the SNP did pretty badly. The two versions of "normality" I referred to earlier now both nervously wonder which version is reality is real, and how the electorate in Scotland will now engage in a "British" political event. Our danger is that there are two opposing "realities" taking shape within the Yes movement as well.

Our trouble is emotional, though, not logical and we need to think ourselves past it. We wanted to substitute the elections in 2015 for the vote on Sept 18th, not as a strategic focus, but as an emotional one. Those of us who are beyond the most simple loyalty to the SNP need to be clear that this was completely predictable. Both that the emotional focus of the movement would latch onto the elections, and that this shared focus would not be sustainable because the purposes of the Yes allies could not ever hope to coalesce behind a first past the post election campaign in the same way as they could for a referendum vote between Yes and No, Hope and Fear, Good and Evil, Life and Death. (To caricature how we felt about it, if not by much)

Our problem is that the visceral emotions which were good for cohesion in the referendum campaign now contain the seeds of destruction for a further alliance, but this danger will become real only if we try to put that shared focus where it doesn't belong.

It is clear now that the SNP, understandably, are going to go into an un-nuanced and , they think, decisive fight with Labour for political hegemony in Scotland. This may well be disappointing to some of us but we'd be children if we found it surprising. It is also hardly surprising, in a first past the post election, that there are SNP candidates who already resent the potential votes for the Greens and the SSP that might prevent them taking some devoutly wished for Labour scalps. These are both sentiments I heard expressed in the two big rooms on Clydeside yesterday.

The answer, I think, is not to ask the SNP not to act like the SNP. Part of it is, however, to ask that they take a little further their offer to parachute non or recent SNP members into candidature in certain constituencies. (Tommy Shepherd, Aamar Anwar and Lesley Riddoch have all been asked, and only one of them said in public yesterday that they weren't going to go for it.) Though this concession is already a big one for any political party, and has doubtless caused no little bitterness at these Johnny Come Latelies in some constituency parties, I don't think I can exaggerate how positive an impact it would have on all those highly intelligent, articulate and motivated activists who gathered at the RIC Conference if the SNP could find room for Maggie Chapman (for example) to run for the Greens in even one constituency without the SNP standing against her.

That is probably a step too far, but that it is almost certainly too big an ask is itself a measure of the distance that we have already invisibly travelled since September back towards a version of political "reality" that is disconcertingly familiar to some of us, even while it is comforting to others. The buoyancy of the SNP is no longer felt to be a universal boon to the broader Yes Alliance, and that is the elephant that, like George Orwell, we need to face down and shoot. We should not expect the SNP to do it for us. And we should not blame them too much for not seeing it as their problem.

And if it is a forlorn hope to ask for a formal electoral pact, then we need another way to use the confidence we acquired in the campaign to come up with a vision that goes through and beyond the emotional focus of the next "big thing" in may next year.

The answer to our short and long terms problems, I think, is to do what we turned out to be good at in the referendum campaign. And that, to our cultural surprise, was the "vision thing."

20:20/2020 - THE VISION THING

People have been chucking around dates for the next referendum pretty wildly online, and some were even doing a bit of that yesterday at the RIC, +and I thought that was a bit daft until yesterday.

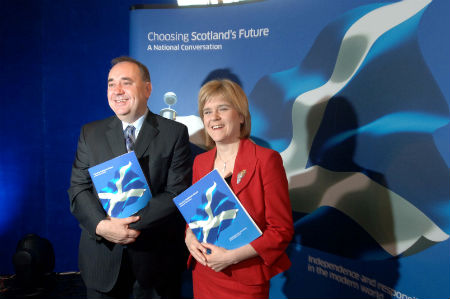

To explain why I've changed my mind, I want to focus first on something that Nicola Sturgeon said that I think we can all agree on as maybe being the foundation for the next stages of the campaign, for continuing and defining what "it" might be.

I started this year by latching on to the clarity of Jim Sillars' line about the people of Scotland becoming sovereign for the first time in our history for 15 hours in September...and voting as to whether or not we wanted to give it back.

What happened, Nicola Sturgeon said is that we voted No but we kept the sovereignty. It turned out that the vote did not mean what any of us thought it did, The campaign itself established Scotland as a distinct democratic polity.

We must act, I take this to mean, not as if we won the vote, but as if we won something far more precious, something that always had to come first before we could start calling ourselves, and living in, a new nation. We won ourselves. We won autonomy. Power, or powers, are incidental. They come later. We lost the vote and achieved nationhood. The bean counting will wait till another day.

In order to make the case that that is what we did to those who doubt us, let alone those who hate and despise us, we have to act as if it were undoubtedly already the case. We will win our sovereignty in exactly the same way as the suffragettes and the gay movement made their strides towards equality. By acting as if we'd already got it.

Now within that achievement, as an already sovereign people who lack the powers, as yet, to match that sovereignty, we can take the immediate heat off either the Westminster elections or some putative immediate re-run of the referendum. We can learn a new perspective and accustom ourselves to the light of a different normality. And say to ourselves that the 2015 election will be an indicator, a sign, of what that new reality looks like.

This acting "as if" may be an electoral strategy to Nicola Sturgeon. It is also a defining imperative for those who came to the RIC conference. It is the key of the vision thing. It means we can start taking the steps we need to address our problems of poverty and education and health within a vision, with a hope of fundamental change to come to inform and empower immediate action in the here and now, And, crucially, it means we can treat elections LESS seriously, in a way. As tactical stagfing posts...not as substitutes for another referendum, or wishes that the last one had gone differently.

Our focus as a movement has to go beyond and through political events, using them as they come up as staging posts towards the vision thing. May 2015, and then the Holyrood elections in 2016, then the local elections in 2017 and a possible EU referendum that same year, and beyond that to the congruence of both Westminster and Holyrood elections in 2020. Each of these "events" can be a staging post to what remains the common goal of independence. Each of them demands a specific idea to meet a specific tactical goal within the broader strategic campaign which is at least, I think, six years long.

In this way we can define "it" as being the same goal as the one we shared in September. Another Scotland is Possible. And there a series of steps we can take right now and in the short term and the medium term not to magic it into existence with a single magical wave of the electoral wand, but to begin to build it here and now.

The SNP is a machine for winning elections. We need that. We also need the ideas that will hold ALL political parties to a standard of thought and hope. We need to be smart, but we should be confident enough in a defined and yet sufficiently distant common goal that we can agree, while also agreeing to disagree and to dream.

20:20 vision for a 2020 referendum. Why not, just for the sake of an organising focus, work back from there? It's far enough away form agreement. It is numerically and symbolically appealing...It acknowledges that the two cultures that crystallised in this country in 2014 will take some work and time to coalesce into the absolutely decisive result (60% + Yes) that we would need.

"It" - the Road - Looks Like This.

With the 20:20 vision as an agreed, limited, and medium term focus, we can look at the upcoming political events as well as the crying social injustices we need to fight every day, from a perspective that acknowledges the need to a shared aim and the need to get on with life and hope and ideas in the meantime. If we take the weight of EVERYTHING off the 2015 election, then we can look to the 2016 election,to Holyrood, under a proportional system, as being the place for different and more generous aspirations than the sole and immediate aim in 2015.

Tjhe aim is 2015, from this perspective is to further signal and cement our transformation as a country, as a democratic polity a place where, to paraphrase a thought we heard a lot at the RIC yesterday, to hope doesn't seem so radical any more.

But if hope for the medium term is not to hobble our chances in the immediate term, we must use the confidence and quality of the thought so often displayed from so many different and opposing voices yesterday to find an appropriate focus around which we can agree to agree while we agree to differ.

There was talk yesterday of identifiable shared values, of an agenda of attacking poverty and not the poor, of democratic engagement in education, housing, electoral reform It was the small practical ideas, like Lesley Riddoch's idea of holding our own ballot for sixteen and seventeen year olds, that got the most convinced and convincing response. It was the aspiration to build public housing that young professionals would fight to be in (from Robin McAlpine) that seemed the best received to me. Because they were both smart both symbolically and practically. There is no way that our movement should sacrifice the radical vision thing that among other things, can be a litmus test against which all parties in the upcoming elections should feel obligated to address, and against which they can be measured and to which standard of hope we should encourage the electorate to hold them.

If what happened to us teaches us anything, it is that democracy and bean counting are not the same thing. Change is a culture, not an event, sovereignty is a state of being, not an act of counting, and elections and referenda only seem like the be all and end all to those whose vision of democracy is equivalent to buying this or that bar of soap at the Country Living Fair.

But even as we hold up that standard that partakes of our belief in the future, we should not lose sight of the present aim. And that means we take every seat we can off every Unionist party by whatever means necessary even if it means holding our noses to vote SNP in the same tactical way we used to hold our noses to vote Labour in the the nobler, greater aim if kicking the Tories out.. It would be enormously helpful, in that context, to run someone other than the SNP in certain seats...that would mean we wouldn't have to hold our noses quite so hard...but we should have the confidence, Greens, SSP or others, that all votes are tactical and determined by our greater shared aim...which is for a Scotland where pour aspirations can become more than aspirations. Our feelings of party loyalty must matter much less than accepting, for this one time only, perhaps,,, the nature of first past the post, which is that the winner takes all.

Ironically, of course, Labour will appeal to the same anti Tory logic to what effect we still can't know. But, a big part of the continuing case for Independence, after the 2015 election, will depend on how the SNP MPs, in whatever numbers, behave in relation to whatever shakes down at Westminster. Their conduct then will be decisive, I think, in converting No voters to a Yes in a future referendum. I think a statement of shared values and social priorities from the broad movement will be helpful, if not crucial, in informing that behaviour and those prospects.

In 2016, in complete strategic contrast, a proportional vote for Holyrood will, I sincerely hope, transform our parliament with the same sense of freshness and hope as did the election of all those Greens and SSP members in 2003, but this time with a sense of common purpose with the shared administration of the Scottish government. That is certainly what I'll be working for. To be personal for a moment, I joined the SNP until May...I will do all I can to help them win the Scottish bit of the UK election in May, mainly to establish that now and forever elections in Scotland, in the UK constitutionally or not, are now games with entirely different set of rules. . After that? Different ball game. All bets are off. The greens? A new left party? A revived SSP? Could be! I understand how this kind of thinking will be difficult for those committed to a specific political party, but I think how I think will also be how the voters think and all the parties, the SNP included, better prepare themselves for the new normality having a few surprises in store.

Some of the animation in both big rooms on Clydeside yesterday was suspended. It needs direction both to cope with the economic and social crimes committed on our people every day and to keep hope and belief in change alive for as long as we'll need to take the next step of our journey through the early, difficult days of a better country. I saw reasons to be wary, which I've identified in this article. but on the other hand, the wit and invention and the passion I saw gave me no grounds to doubt that difficulties, as Shakespeare put it, are but easy when they are known. For all we were indulging a little in wishful thinking yesterday, there is nowhere on earth I'd rather have been.

As more than one person said yesterday, there has been no better time to be in Scotland. And won't be until next year, and the year after that and the year after that...

Sunday, 23 November 2014

Sunday, 16 November 2014

It's No Game.

I have seen two kinds of expert reaction to Nicola Sturgeon's own "vow" on Saturday that the SNP will under no circumstances "put the Tories in power" in the event of a hung parliament after the general Election next year. One, of straightforward puzzlement from the Westminster games players, who cannot see why anyone would nail their colours to the mast like that. After all, the rules of the Coalition game have been set for years by the Liberal Democrats...that the party will await the "will of the electorate" before sticking their opportunistic colours to whichever ship seems to be heading for governmental waters. By the rules of that game of tease, it makes no sense to declare in advance what you will or will not do.

It would seem that the declaration from Nicola Sturgeon was announcing a different game with a different set of rules.

We have also heard from several commentators their analysis of the next concomitant step along the path- that the SNP would help Labour to form a government - and why would an elector who wanted a Labour government not just vote Labour.

Again, within the rules of the game as it has hitherto been played, up till and including the last Holyrood election, where the anti-Tory Scottish vote distributes itself tactically distinctly between "local" and "national" elections, that logic cannot really be faulted.

It follows then, I think, that Nicola Sturgeon's version of the Vow must be part of a different game with different rules. It is in fact based on a gamble on the intangible. (Who knew that Nicola liked a flutter as much as her friend Alec?) The bet in question being whether or not,having declined to change itself profoundly on the 18th of September, Scotland really did profoundly change on the 19th. That the game is not the same any more. Not that tactical voting has ceased to differentiate between Westminster and Holyrood elections, but that voters now tactically calculate that the best way to defend ourselves from the Tories, and , crucially, from neo-liberal Tory values , is no longer to participate in the UK while hedging our bets in Scotland, but to move all of our electoral chips onto one side of the table. And vote SNP in both

If the Scottish electorate go for the pitch that an SNP vote in Westminster and Holyrood elections is better tactics than a Labour vote in one and an SNP vote in the other, then there really has been a profound change. That tactical choice would reflect an existential understanding on the part of the electorate that Scotland is now and forever politically both entirely distinct from the UK and entirely its own polity, and its own democracy. And that therefore the relationship with the UK has itself transformed. Labour's own gamble that devolution would consolidate its control of Scotland while maintaining a loyal block of votes in Westminster will be proved, to use an old 7:84 word, a bogie.

To get classical, the die will be cast, Scotland will have crossed the Rubicon. (Or the Solway) Make no mistake, if the SNP can cross the threshold where the first past the post achieves electoral system stops suppressing the small party and rewarding the big one, if they can keep their current level of support in the polls and the Central Scotland,Labour seats really do start falling like nine-pins, then on a far deeper level than mere electoral fortunes, we will be living in a different country.

On one level, it may well be that the "No Pact with the Torys" pledge is mere electioneering. That it is intended to force Jim Murphy to take Scottish Labour further to the left even while the two Eds down South do their best to impersonate Osborne on economics and Farage on citizenship. Murphy will then be an easy target for the accusation that he is promising a socialist government in Scotland when his entire Unionist position means that he can offer no such thing. Indeed, the logic of labour as a socialist alternative to the SNP only makes sense in an independent Scotland. Sturgeon is also gambling that the Scottish electorate are savvy enough to suss out that the left opportunism that jolly jim seems to be offering currently is either the crassest and most obvious hypocrisy or is actually a declaration of Indy by an unexpected pathway... It may be, machine politician that she is, Nicola Sturgeon is simply continuing the superior tactical Gnous that the SNP have used to make a succession of Scottish Labour Leaders look silly for getting on for a decade now.

But their tactical superiority indicates a deeper truth, and it is this truth that I think the SNP are now "acting as if" they believed. That they bring their A game and their A team to Holyrood because it is now Holyrood that matters. The SNP, at the time of devolution were, like the others , a Westminster-model Party. They were formed through Westminster politics, and still had that shape in the uneasy first years after devolution. But they have now adapted themselves in to being a Holyrood Party that plays tactics at Westminster. They are doing this now with complete conviction because they believe in the depths of their bones that the Westminster game has finally become someone else's business. That keeping the flame of social justice burning in the UK as a whole is no longer best served by holding our noses and voting Labour. That it is only a matter of time and a tactical nip and tuck till Scotland achieves home rule in some shape or constitutional form and within all the caveats and conditions of our interdependent islands and continent and world.

The Anti - Tory Vow is a manifest interpretation of the No vote as being a vote for "Not Yet", as a vote, without any real conviction,to give Westminster one last chance, just to be on the safe side. It is a vote then , based on a belief in something. And that in itself may well be enough to make the current rather wild poll predictions come somewhere near to coming true in May.

I believe that people on both sides of the Yes/No divide want to believe that we can change the country and ourselves. And that if we act as if we had faith, we might just pull it off. And that might just be enough

Tuesday, 4 November 2014

From Global Dispatches - May 2014

Signal Rock

At the bottom end of Glencoe, a car journey down which in any weather partakes of both the sublime and the terrible, is an underdeveloped and underwhelming tourist attraction which goes by the name of Signal Rock. You reach it by a cleared pathway down and into the Forestry Commission planted woods a mile or so from the Tourist Information Centre.

At the bottom end of Glencoe, a car journey down which in any weather partakes of both the sublime and the terrible, is an underdeveloped and underwhelming tourist attraction which goes by the name of Signal Rock. You reach it by a cleared pathway down and into the Forestry Commission planted woods a mile or so from the Tourist Information Centre.

Surrounded as it is by trees grown much taller than it, Signal Rock affords no great outlook on what is one of the most spectacular landscapes in Europe. It is only by a wee, white pointy sign that it is singled out for your attention at all.

An explanatory notice board tells you that the rock derives its current name from a legend, undoubtedly untrue, that it was from here that the signal was given to begin the massacre of the MacDonalds in the nearby village in 1692…the name probably came about in the 19th century, when, along with the rest of Scottish history, the Jacobite resistance to the Hanoverian Succession had been safely relegated beyond dangerous memory into picturesque and sentimental myth.

The trees insensitively planted around it, as they were over much of Highland Scotland in the Twentieth Century, when the postwar needs of the Forestry Commission and the mass housing of the fifties and sixties trumped those of Celtic Romanticism, now render the place invisible, and lead to some scepticism that this was ever a vantage point from which to send a signal to commit tribal murder in the name of the Crown.

The Gaelic name of the stone, by contrast, Tom a’ Ghrianain, or Hill of the Sun, suggests ancient sun worship…which, given that the trees weren’t there back then and the Glen faces East to the rising sun as well as West to the sea from which the Gaels arrived on this island, certainly seems more plausible. It is worth reflecting, however, that the idea that a bit of Scotland was once dedicated to Heathen Rites was unthinkable until recently, when the covenanted status of Scotland as the true home of God’s chosen people is a rather less persuasive self- identification than it used to be – even if we do retain a certain lofty smugness as a consoling (to us) and irritating (to everyone else) national characteristic.

The different names and significances that history, including its most recent and ecologically sacramental version, has given to this hopefully “one day to be fully appreciated as really quite interesting” chunk of Highland Landscape can stand, I think, for the incoherencies and half -truths of the recent conduct of the Rising of 2014. There are layer upon layer of mutual incomprehension, miscalling, misspeaking and mishearing going on in this campaign that reveal sedimentary layers of dysfunction in the political geology of Great Britain.

A Tale Of One Treaty – Twice

Going right back to when the Treaty of Union was signed in 1707, shabby little deal that it was, the same arrangements have carried utterly different meanings and levels of significance depending on who’s looking. From the beginning of the Union, the Scots have taken the details much more seriously. The English appear not really to have read the treaty when they signed it, if their actions in the immediate aftermath are any indication. Those Augustan Englishmen seem to have appended their names in much the same spirit of “Yeah, whatever” with which their successor, (and descendent of a Scottish signatory of the Treaty) David Cameron signed the Edinburgh Agreement on the referendum with Alec Salmond in 2012. Indeed, I would be surprised if many of my English readers are even aware that the two governments have agreed between them not just a legal basis for the referendum process but a promise of mutual respect for its result , and that in its aftermath, both sides have undertaken to do their best for the inhabitants of what would then be our two different countries.

Going right back to when the Treaty of Union was signed in 1707, shabby little deal that it was, the same arrangements have carried utterly different meanings and levels of significance depending on who’s looking. From the beginning of the Union, the Scots have taken the details much more seriously. The English appear not really to have read the treaty when they signed it, if their actions in the immediate aftermath are any indication. Those Augustan Englishmen seem to have appended their names in much the same spirit of “Yeah, whatever” with which their successor, (and descendent of a Scottish signatory of the Treaty) David Cameron signed the Edinburgh Agreement on the referendum with Alec Salmond in 2012. Indeed, I would be surprised if many of my English readers are even aware that the two governments have agreed between them not just a legal basis for the referendum process but a promise of mutual respect for its result , and that in its aftermath, both sides have undertaken to do their best for the inhabitants of what would then be our two different countries.

Now for a Scotsman, any Scotsman, especially one of an historical bent like Alec Salmond, to sign a treaty with the Prime Minister of the UK, to be treated, however formally, contingently and legalistically, as an equal partner to an agreement like this, is a huge deal. Hence Alec Salmond’s insistent reminders of its provisions, especially the undertaking of both parties to act in the interests of both populations. (He thinks it might be worth reminding George Osborne that a trade war, for example, wasn’t even in the fine print.) Hence also the House of Lords airily dismissing the terms of the agreement as being not constitutionally binding. No matter what we might think we’ve just voted for, it is the opinion of their Lordships that the independence of Scotland will remain in Westminster’s gift

“Yeah, whatever” indeed.

For the Scots, the treaty of Union is the founding document of the UK, while the UK effects to believe that our voting to end that treaty has no legal consequence. For Salmond, the Edinburgh agreement is an amendment to that quasi-constitution. For Cameron, such a thought would barely merit a puzzled blink. At every level, from day to day campaigning to the largest imaginable historical questions, this is a dialogue of the deaf.

One Campaign, (at least)Three Realities

The day-to-day need for sign language lessons was recently exemplified for me by Patrick Wintour, one of the Guardian’s excellent team of lobby correspondents at Westminster, reporting that the Tories, aware of their unpopularity in Scotland, are relying on the “Labour Machine in Scotland to deliver their voters.” The idea that Labour politicians from Scotland are going around London giving the impression that they have anything like a machine left up here, let alone a cohort of tame voters at their disposal argues for a disconnect from reality that is either pathologically mendacious or just plain pathological.

The day-to-day need for sign language lessons was recently exemplified for me by Patrick Wintour, one of the Guardian’s excellent team of lobby correspondents at Westminster, reporting that the Tories, aware of their unpopularity in Scotland, are relying on the “Labour Machine in Scotland to deliver their voters.” The idea that Labour politicians from Scotland are going around London giving the impression that they have anything like a machine left up here, let alone a cohort of tame voters at their disposal argues for a disconnect from reality that is either pathologically mendacious or just plain pathological.

Indeed, while the Tories are right to think of themselves as politically toxic to Scotland’s political eco-system, it seems that none of the Westminster parties seem ready to acknowledge that this toxicity has decidedly spread. They have been deceived by the anti-Tory Labour vote that Scotland has delivered at every general election since the sixties into thinking that delivery is unconditional. The Labour Party has changed itself quite radically in order to remain viable as an electoral choice in the South of England outside London. But to follow through the logic that this accommodation to Tory England …. has led Labour to sharing some Tory toxicity in Scotland is apparently beyond their ken. Hence, they have not reported to their senior partners in the union that what was once a principled Labour vote has become tactical voting for UK elections only. Scottish elections, now as important culturally as are UK elections, are much more likely to go the SNP’s way, especially if we vote No in September. Who can protect us best from the Tories? is the question we ask ourselves. SNP in Edinburgh, Labour in London, has been the answer up to now. But a tactical vote is a changeable vote. The old certainties don’t apply any more. The status quo might be on the ballot paper in September. It is definitely not on the cards.

Labour people here look at you blankly when you say this kind of thing , as if, as we say in Scotland, you had grown an extra head, but to all but the most myopic of sectarians, it’s perfectly obviously true. This is a source of sadness to most politically engaged people in Scotland, who still feel an emotional attachment to the movement of which the Labour party used to be the head. Nowadays, however, to get theatrical for a second, if it is the Labour Movement in Scotland that is the central character in the modern tragedy of “ The Union” , then we are already well into Act Five, no matter how unaware of his approaching doom the hero is.

The Sermon on the Pound

Of the specific events of the Referendum drama as it currently unfolds, the most important, indeed definitive event on the No side of the campaign, has been the speech given by the Chancellor, George Osborne in Edinburgh in March and the unanimous declaration by the senior finance spokesmen of all three main political parties in the United Kingdom that they would unequivocally in no way tolerate even a hint of the possibility of negotiation over sharing a currency union with some putative future independent Scottish state. Furthermore their refusal in principle to pre-negotiate the terms of this monstrous and unlikely secession from the greatest democracy the world has ever known is now predicated on the absolute pre-negotiation position that in no way would any future government of the remaining United Kingdom ever entertain the merest hint of any conversation on the subject. No way, not now, not never.

Of the specific events of the Referendum drama as it currently unfolds, the most important, indeed definitive event on the No side of the campaign, has been the speech given by the Chancellor, George Osborne in Edinburgh in March and the unanimous declaration by the senior finance spokesmen of all three main political parties in the United Kingdom that they would unequivocally in no way tolerate even a hint of the possibility of negotiation over sharing a currency union with some putative future independent Scottish state. Furthermore their refusal in principle to pre-negotiate the terms of this monstrous and unlikely secession from the greatest democracy the world has ever known is now predicated on the absolute pre-negotiation position that in no way would any future government of the remaining United Kingdom ever entertain the merest hint of any conversation on the subject. No way, not now, not never.

In this way, it has become clear that of all the uncertainties of the future arrangements on an Independent Scotland – about passports, about our becoming a base for Al Qaida, and our vulnerability to attack from space, all of which have had a mention – it is the nature of the Pound in your Pocket that Westminster has judged to be the most dramatically convincing uncertainty that the Union side can first create and then criticize the Yes side for.

The pronouncement of the parties was further underlined by the unprecedented public release of the normally secret advice given to the UK Treasury and the Chancellor, George Osborne, by the senior civil servant Sir Nicholas MacPherson to the effect that the suggested currency Union was both impractical and undesirable, which is British Civil Servant Speak for “ hell in a hand basket.”

Sir Nicholas is Scottish, as is Danny Alexander, the senior Liberal Democrat economic spokesman and member of the coalition government. He is also close to Alistair Darling, also Scottish, the former chancellor and nominal leader of the No Campaign. It seems that George Osborne for the Government and Ed Balls for Her Majesty’s loyal opposition, simply signed off on the strategy, trusting to the collective Caledonian chutzpah of their colleagues.

Trouble is, it was Darling, who, in January 2013 on the BBC’s Newsnight Scotland, was heard to opine that just such a currency Union as was later proposed in the SNP’s White Paper was obviously the most logical arrangement in the unlikely event of independence. Mr Darling may now be saying exactly the opposite, but no one thinks he has really changed his mind. Indeed it is unworthily speculated that it was almost certainly Alistair Darling himself, as a chief cog of the aforesaid Labour Scottish Machine, who came up with the strategy of absolute denial of the very currency arrangement that he had said was logical a year and half ago – that he has advised that the most logical arrangement be taken off the table precisely because it is the most logical, and because the SNP, as centre-left business-friendly pragmatists of exactly the same stripe as himself had predictably come to the same conclusion on the matter that he had.

The Byzantine twists of the above may seem to bespeak a depthless cynicism, but I think rather that it is one more piece of evidence as to the distortions of the already entirely distinctive Scottish political psyche that outsiders in Westminster might find instructive. Clan warfare of the Campbell/MacDonald ilk seems to have has passed its venom into our politics, where Labour and SNP politicians who agree almost exactly on almost every policy have come to loathe each other so tribally that any public conversation about even trivial matters looks and sounds like a battlefield from which the civil servants have thankfully removed the weapons.

The nearer we get to becoming an actual democratic polity, the more hysterical and pre-democratic the argument about it gets. The irony is that Currency Union is not even a universally agreed aim of the Yes campaign. Some Yessers (the most traditional nationalists, by and large) are very happy about the idea of a new or restored Scottish currency. Yet others are relaxed about using a Scottish pound informally and temporarily pegged to Sterling in the meantime, yet others with a quiet drift towards the hopefully by then …. recovered Euro Zone. While the principled core of the No vote, who wouldn’t vote for independence if it started raining banknotes of any denomination, (which is probably about 20% of the electorate), and the 35% who are irrevocably already committed to Yes no matter what, are, on the currency question, like on most questions of the crystal ball variety, relaxed and indifferent.

The Yes Scotland Campaign, though the SNP are of course dominant, is itself a rather loose and so far harmonious coalition of very diverse aspirations that maintains a generally rather woolly and tactically non-specific approach to the general and shared aim of political sovereignty. (The No campaign are rather more given to leaking and anonymous briefing against each other. ) We’ll work it out later, more or less defines the Yes campaign’s provocatively relaxed approach to answering the increasingly shrill and indignant demands for post-indy specifics put to them by the No campaign. It’s a question of appropriate trust in the wisdom and resources of Scotland and its people, they smile.

Who Are the Maybe Nay Sayers?

But the vote will not be decided by believers. Rather, it is the 45% chunk of Scottish opinion and character that has yet to be persuaded in principle either way who count for most, and while they probably lean to Yes sentimentally for the most part, they are vulnerable to the changing tides of optimism they find on the internet, and the non-stop despair they get almost everywhere else in the media. The Union will ultimately rely on No votes from those who are not opposed in principle to independence, but can be successfully frightened of its intrinsic uncertainties, and it is all very well for the Yes campaign to argue that difficulty and complexity are arguments for and not against democracy and self- government. The dominant paradigm of democratic politics is the marketplace of the spurious certainty, and that paradigm may or may not break in time for a Yes vote to gain the confident traction it will need.

But the vote will not be decided by believers. Rather, it is the 45% chunk of Scottish opinion and character that has yet to be persuaded in principle either way who count for most, and while they probably lean to Yes sentimentally for the most part, they are vulnerable to the changing tides of optimism they find on the internet, and the non-stop despair they get almost everywhere else in the media. The Union will ultimately rely on No votes from those who are not opposed in principle to independence, but can be successfully frightened of its intrinsic uncertainties, and it is all very well for the Yes campaign to argue that difficulty and complexity are arguments for and not against democracy and self- government. The dominant paradigm of democratic politics is the marketplace of the spurious certainty, and that paradigm may or may not break in time for a Yes vote to gain the confident traction it will need.

(Then again this may be a phenomenon of human politics not just of modern models. Had a plebiscite been feasible in the 13 colonies in 1775, even George Washington, who described independence from Britain as “a leap in the dark” might have found himself in the Better Together Camp. Like most de-colonizations, like in Ireland and India, the independence movement in America relied finally on the British doing something both high-handed and stupid. I wouldn’t bet against it, but it hasn’t happened yet.)

Positive support for the Union is concentrated around the anxieties of those with most to lose, those with pensions, property and investments and the careers of their off-spring in London to worry about, and the strategy on the currency was designed, as most of the strategies of the No Campaign have been, to work on those entirely understandable, if less than romantic, fears of personal and familial loss being the unacceptable price of democracy.

The deep and historic irony of this is that the middle class in Scotland – the lawyers, the doctors, the clergy, the educators, as they were at the time of the Union – have always actually been in favour of independence from UK control. But only independence for themselves, not for their fellow Scots or Scotland as such . The terms of the Treaty of Union meant from the outset that the law, the kirk, the schools and Universities retained their functional distinctiveness and indeed, independence from the amalgamation of merely political power. The kirk provided universal schooling against the wiles of the Papacy, and the land owners kept owning the land, indeed kept hold of it with the help of the rather more stringently feudal character of still distinctive Scottish law. Between them, they fostered the growth of an argumentative, egalitarian and yet sheepishly unambitious bourgoisie.

In the 19th century, this middle class was added to by the bureaucratic, mercantile and military employment prospects of the Empire and it’s civil service, so eagerly sought and filled by Scottish lads o pairts – Scots at less than a tenth of the population of the UK provided fully a third of the colonial bureaucracy.

In the twentieth century, the secretariat of the welfare state, local government, nationalized industry and industrial scale education was a similar pool of opportunity for the advancement of a new clean-collared echelon of Scottish Labour. Thus evolved a single unelected and anti-nationalist national hegemony within an unsupervised outpost of a British state that granted functional independence to this succession of Scottish elites, who could thus remain aloof from democratic oversight both from Westminster, which didn’t care that much, and, more importantly, from an electorate in Scotland which didn’t count for anything.

This was the fiefdom from which first the Scottish Unionists and then Labour drew their “deliverable” vote, and while the Protestant Ascendancy, then the welfare state and mass employment and housing lasted, they did indeed deliver a passive, un-consulted, barely visible and slavishly reliable electoral base. That this political base began to disintegrate, along with the collective provision and mass employment on which it was founded, was an obvious sequel, and it seems curious that Labour, for example, should have been taken so much by surprise when their bondsman sought alternative representations in the SNP and the Green party in recent times. But they were. Even having lost two elections in a row they barely seem to credit it and act as if some terrible mistake will soon be corrected and everything will return to normal.

Scotland has been governed by a series of local elites with power derived from subservience to the bigger, wider, British elite who they have never minded not electing because they’re not elected themselves. They know, our local hegemons, that independence from London rule is a good thing. It always has been for them – in education, health, the law, and the kirk . That’s how they know it is too good for the rest of us. It is their pre-democratic sphere of privilege, safe from London because un-regarded by London, that is seriously threatened.

This is why from the Scottish Law Society to the BBC and CBI as well as Labour dominated local government, the powers that be in Scotland are in the No camp. Devolution has already exposed them and made them vulnerable and scrutinized in way they’re not used to, and they fear that independence might finish them. In short, it’s not so much independence they’re afraid of as democracy. They think democracy might sink the ship. There is something rather primitive at the base of our democratic under-development. The Scottish Middle Class, which includes the Labour-voting, publically employed middle class, tends to support the Union because they don’t ultimately trust the people in the next street.

As the Community Activist Nick Durie put it in a recent blog:

“ On the rare occasions in my canvassing that I’ve met strong NOs, they have always been angry, vituperative, and visceral and above all ENTITLED. I think it’s fair to say that the NO campaign is “about” entitlement. Entitlement to forever control Committee Scotland. Entitlement to forever rule vast tracts of our rural landscapes. Entitlement to scrap the welfare state – about the only palatable part of the British Empire. Entitlement to the kind of economy that leaves one third of households in Glasgow workless. Entitlement to be as corrupt as they feel like. Normality in Scotland is very much not the normalcy of a Northern European country. In a place that produces more oil than Kuwait, 2400 vulnerable people freeze to death every year. There is nothing like it across Northern Europe. And these NO campaigners feel entitled to preserve this state of wounding iniquity? As this mask slips, and this rank entitlement is laid bare, the nae campaign is becoming little more than the funerary cries of an old order of corrupt elites. ”

“ On the rare occasions in my canvassing that I’ve met strong NOs, they have always been angry, vituperative, and visceral and above all ENTITLED. I think it’s fair to say that the NO campaign is “about” entitlement. Entitlement to forever control Committee Scotland. Entitlement to forever rule vast tracts of our rural landscapes. Entitlement to scrap the welfare state – about the only palatable part of the British Empire. Entitlement to the kind of economy that leaves one third of households in Glasgow workless. Entitlement to be as corrupt as they feel like. Normality in Scotland is very much not the normalcy of a Northern European country. In a place that produces more oil than Kuwait, 2400 vulnerable people freeze to death every year. There is nothing like it across Northern Europe. And these NO campaigners feel entitled to preserve this state of wounding iniquity? As this mask slips, and this rank entitlement is laid bare, the nae campaign is becoming little more than the funerary cries of an old order of corrupt elites. ”

The Law of Unintended Consequences

Even before the leak from what the Guardian’s Nicholas Watt called a senior UK minister that, after all, if the unthinkable should actually happen on September 18th, on September 19th everything would have to be on the table to be talked about, it seemed that what had appeared to be the rather weak response of Alec Salmond to the Westminster Currency Dictat – that the Unionists were lying and that of course there would be negotiations – was bland and complacent even for him.

Even before the leak from what the Guardian’s Nicholas Watt called a senior UK minister that, after all, if the unthinkable should actually happen on September 18th, on September 19th everything would have to be on the table to be talked about, it seemed that what had appeared to be the rather weak response of Alec Salmond to the Westminster Currency Dictat – that the Unionists were lying and that of course there would be negotiations – was bland and complacent even for him.

But it turned out, against all preconceived political precedent and wisdom, to have been exactly the correct response. He said Westminster was probably bluffing and according to opinion polls, 45% of voters in Scotland believed that they probably were. (This was the poll that prompted the intervention from the now never-to-be- named UK government source).

Worse, perhaps, the strategy that had rather flopped in Scotland struck a strong political chord in England, whose impatience with the chippy and perpetually complaining Scotch is now reaching the status of an actual, live political issue. However desirable in pragmatic terms a currency union may once have been, as Mr Darling testified in another life, it has been made into a political impossibility not north, but South of the border.

That the same government pronouncement on this issue should meet with two entirely different and indeed opposite political responses on different sides of a border should not be in and of itself surprising. But when it is the significance or otherwise of that border that is precisely the issue, this divergence matters rather more. The whole feel and character, let alone discourse and understanding of British and Scottish politics do seem to be differentiating to the point of mutual incomprehension. It may be that a Yes vote in September is merely a recognition that the Union is already dysfunctional, that on many if not most important levels, “separation” is already a fact. This is actually becoming more and more difficult for the Unionists to argue against. They seem to be the ones with their finger in the dyke when there’s a storm coming.

To give a recent example, the week after UK Labour leader Ed Milliband appeared at the Annual Scottish Labour Party Conference in March to argue that a vote to keep the Union was a vote for social justice, with no sense of irony at all, the very next week he led the UK Labour Party in the Westminster parliament, including its loyal Scottish members, into the voting lobby of the Commons to vote with the Tories for a legal and permanent cap on welfare spending.

To quote Iain MacWhirter in the Glasgow Herald, the best-selling daily in Scotland : “There are now only two things the Tory and Labour front benches in Westminster agree upon: that Scotland should not be allowed the pound after independence, and that social security spending should be capped permanently, irrespective of need or changing circumstances.”

From the perspective of the Westminster village, to vote this way was for Labour a genuinely wizard wheeze to neutralise Tory attacks on them as being soft on welfare, the party for the scroungers. Given that the vote received next to no coverage next day in the national press, they could congratulate themselves on a political bullet well dodged.

However, from another point of view, from the perhaps equally parochial village perspective of the old British left, the Labour party voting with the Tories to enshrine the principle that the transient needs of capital outweigh the historic obligation of a state towards the welfare of everyone who lives there was a catastrophic and terminal betrayal of everything that the post-war consensus of British-ness had supposedly stood for. It was, in effect, the coup de grace delivered to the already bloodied and dying remnants of British Socialism, and the fact that the execution was both casually done and self-congratulatory surely dramatizes the distance that the party of Clement Atlee has travelled since 1945, or indeed from 1979. And if it was that post-war social consensus that they felt they could so casually disregard in order to avoid unfriendly headlines in the Daily Mail, then that consensus was also the glue that held the post-imperial political Union of Scotland and the UK together. You’d have thought they might have noticed that they were putting that too out of its misery.

The British social revolution of 1945 – which gave us the National Health Service and the principle of universality and universal provision for the vulnerable as the centrepiece of the welfare and taxation system devised by the Liberal William Beveridge and the Welsh socialist Aneurin Bevan, among others, was the foundation of the social contract of British self-identification as “all being in this together”. It was itself the product of the collective experiences of the depression and of the war. That was the Britain I grew up in. And surely everyone can see it isn’t there anymore. Surely everyone can see that the Britain which Scotland has been asked to remain part of no longer exists.

This is the political substance behind the very widespread feeling here in Scotland that we are not so much leaving as we have already been left. And the fact that this feeling seems beyond the comprehension or empathy of the political party that made that now-broken consensus is itself an argument that the fellowship which one might expect to be the chief appeal of the case for the Union is hollow and unconvincing. Unsurprisingly, the Togetherness argument is only intermittently employed, usually with embarrassing results, and is almost invariably immediately dropped in favour of more promised catastrophe, and more veiled threats that if we dare to vote Yes, then our lives will be made “difficult”.

As I write, then, the No campaign have lost the argument and lost the campaign quite decisively. But they may well still win the vote. All the uncertainty peddling still seems, despite everything, to be commanding a lead in the polls and successfully pandering to a streak of self-dislike and self-doubt in us that may be understandable, but is less than encouraging whatever your view of the question at hand. And while negative strategy may well secure the No vote that is being sought, does it not need to be asked, on the Union side, what kind of relationship is it whose only maintenance is in planting fear and insecurity in one of the “partners”? Is winning at the vote really worth the price we’ll pay afterwards if we feel ourselves to have succumbed to the unworthy, fallen angels of our nature? I venture to suggest that such a “Union” is not going to be happy nor stable nor, in the long term, tenable. And that unintended consequence of a negative campaign to keep the Union together is to demonstrate its essential brokenness so clearly that everyone can surely see its dissolution in the near future.

Questions for Next Time if not This Time

Questions are clearly now emerging into general consciousness that undermine the Union on a much more fundamental level than even the binary pig in a poke we’re being offered in September. Is sovereignty in Scotland currently on loan to the UK, or in the permanent gift of the UK? Conversely, can a UK government ever be legitimate in Scotland once you consider Scotland to be a political unit?

Questions are clearly now emerging into general consciousness that undermine the Union on a much more fundamental level than even the binary pig in a poke we’re being offered in September. Is sovereignty in Scotland currently on loan to the UK, or in the permanent gift of the UK? Conversely, can a UK government ever be legitimate in Scotland once you consider Scotland to be a political unit?

Whether we vote end up voting Yes or No, we are going to have local problems in our political atmosphere. It is clear that politics in Scotland has been defined and distorted by the constitutional question, as politics in the six counties of Northern Ireland has been since 1921. The border, once it is in question, becomes THE question.

From the moment that for very first time in history the Scottish electorate were ever addressed as such, as a distinct democratic polity, (in 1979 and the first devolution referendum), the border has indeed been in question, and as in Northern Ireland, we have divided, more or less, into those who seek to see nothing but the constitutional question and those who seek to suggest that the constitutional question is itself nothing. To one side of the debate, every question of culture and society, economy and identity, is viewed through the prism of self-government, contingent on the promise of autonomy. To the other side, any attention at all to these questions is a grudging concession and an obscene irrelevance, a self-interested distraction from exactly the same questions of inequality and our appalling health record, to name but two. And given these diametrically opposed perspectives, proper democratic dialogue is impossible.

This is to put the mutual loathing of the SNP and Labour clans at its most reasonable and principled seeming. At its most distressing, however, our parliamentary procedure, at least at the weekly set-piece of First Minister’s questions, it manifests itself as a screeching, mocking parody of debate or a children’s game of “Geez ma Baw back.” Little wonder Westminster hesitates to intervene. And now with the referendum looming, each side is acting as if the other side will simply agree to cease to exist if and when they lose. Both Labour and the SNP confidently anticipate that the other will disintegrate if we go for Yes or No, but this is surely no more the case than that Scotland will either be physically sundered from or entirely absorbed into the land mass of England.

As a Yes supporter, I believe that our politics can only find a cure from its tribalism when the political sovereignty of the Scottish people ceases being a conditional loan from London of circumscribed but unaccountable hegemony. I believe that once the sovereignty of the people as iterated in the Claim of Right in 1989 is taken seriously, then the argument is over between the UK and Scotland, and that the argument within Scotland will take on a new and less tribal resonance. Political independence, however negotiated and defined, is itself contingent and limited by interaction with the world, and demands discussions of a different order. For me, the No campaign promises more of the same of what is worst and most corrupt in politics on both sides of the border. It is a case only for hiding from responsibility for ourselves, and for abstaining from the world, for accepting that it is much better and safer to disappear, to re-submerge all but the most superficial signs of our identity within the broader British world presence as an offshore adjunct of international capitalism and of American military global reach.

No voters, friends of mine, tell me that a No vote is simply the pragmatic choice in this post-democratic age, and that to abandon the aspiration to collective independence can do no harm to our self-esteem as individuals. After all this is over, they say, we can get back to normal business. After all, some of us are doing fine. Some of us are doing very well. The core injunction for the No vote does seem to be “Don’t rock the Boat”, which may make sense on the First Class Deck, but it also argues for a profoundly pessimistic outlook if that side really believes that what we have now is the best we can possibly do with ourselves.

I remember coming into adulthood in the 1980s, in a country where it felt like the future was all behind it, and whose failure to secure even the measure of autonomy offered it in 1979 left it wide open to a devastating assault on its industrial and employment base , and to a widening and deepening of already abysmal divisions in wealth and health from which it has never recovered, and which redefined its culture as a resistance movement.

I have no way to tell if that’s what would happen again, but even among No voters, I cannot detect any complacency as to the positive prospects of continued Union. “If we try it, they’ll hurt us,” seems to be the unspoken message of Better Together. To which I only ask, “Don’t you think they’re hurting us now? How do you think it will be if we give them permission? If we tell them we’re fine with it?”

How Does It Feel to Hope?

It was only because they thought a No vote was in the bag, that the powers that be not just permitted, but wanted this referendum to happen, more even than Alec Salmond. And that by taking incremental change off the table and pushing us into a crude binary choice this September – they were offering us a chance for change that they were dead sure we wouldn’t take. Thus, the referendum was proffered as a hedge AGAINST democracy, not a concession to it. The power elite wanted, if they could, to deny us all change, or control the change undemocratically if change there has to be.

It was only because they thought a No vote was in the bag, that the powers that be not just permitted, but wanted this referendum to happen, more even than Alec Salmond. And that by taking incremental change off the table and pushing us into a crude binary choice this September – they were offering us a chance for change that they were dead sure we wouldn’t take. Thus, the referendum was proffered as a hedge AGAINST democracy, not a concession to it. The power elite wanted, if they could, to deny us all change, or control the change undemocratically if change there has to be.

But what has happened is that the Yes campaign has revealed and unleashed and added depth and nuance to the desire for change, and created an articulate, popular movement for it. This may or may not result in a cumulative, collective celebration of the restoration of popular choice as a factor in modern politics on Sept 19th.

The thinking that prompted “giving” us the democratic choice for fifteen hours on Sept 18th was designed not to stop Independence – Independence doesn’t worry them per se – it is democracy that is the problem that needs to be squashed, and this anti-democratic impulse is every bit as much embodied in the Elite in Scotland as it is in the Elite down by the great money river.

At the age of 52 I have never known civil society of Scotland to feel as positive, hopeful, inventive and frankly un-Scottish as it does at this moment. Not only is the campaign more or less free of the bogus fripperies of 19th and 20th Century Scottish identity from the black-and-white kitsch of my Scottish television childhood, it is also free of the accompanying gloom of the Calvinist forest of the Caledonian soul. A lot of this unaccustomed optimistic activism is happening in the virtual world – it is online and but it is also in meetings both formal and informal that seem to be happening everywhere – from snatched conversations with strangers on the CalMac ferry to Mull, from Lourdes Primary school packed to the gunnels, to Facebook and Twitter. Douglas Dunn, the poet, used to say that the greatest achievement of renewed democracy in Scotland would be if his first year Scottish undergraduates could summon the self-confidence to ask him questions. Now it seems that nobody is shutting up. We are messaging each other across computer interfaces as if there were such a place as tomorrow, and as if we might have some influence on what tomorrow looks like. In my lifetime, I have never known so many Scots to be as politically engaged.

By contrast, it seems that the only case for the Union is silence. The only mood music is despair, and that if No wins, after all this, having lost the argument of hope, then the morning of September the 19th is scarcely worth contemplating without an arm full of heroin. It would feel like death had won and life had lost.

This summer we should celebrate all the more, then, that we seem, thanks to the work of activists everywhere, in localities and in the global forum of the web, to have stolen the ball off them for a minute. That is worth reflecting on and treasuring in itself. Even before we get to planning the party if (hold your breath) we actually win. And allow ourselves to ….. hope that Scotland really might offer the world a model of a social-democratic, nuclear free, inclusive and equitable future.

Why do you think they are trying so hard to stop us?

Our Bannockburn?

The battle of Bannockburn in 1314 did not, in itself, after all, guarantee Scotland’s sovereignty in the 14th century. It did succeed in making Scotland ungovernable from London except by overwhelming force. I suspect that the referendum, whether with Yes or No majority, especially if the answer is close, will accomplish roughly the same. Bannockburn meant that Scotland’s self-rule was no longer within England’s gift. But it was not until 1328 that Scotland’s right to self-rule was recognised by the then government of England – in the Treaty of Northampton and Edinburgh.

The battle of Bannockburn in 1314 did not, in itself, after all, guarantee Scotland’s sovereignty in the 14th century. It did succeed in making Scotland ungovernable from London except by overwhelming force. I suspect that the referendum, whether with Yes or No majority, especially if the answer is close, will accomplish roughly the same. Bannockburn meant that Scotland’s self-rule was no longer within England’s gift. But it was not until 1328 that Scotland’s right to self-rule was recognised by the then government of England – in the Treaty of Northampton and Edinburgh.

They were about to start the Hundred Years War with France and needed a friendly, or at least quiet, Scotland next door. You can see why the parallels occur to me.

My prediction is that it is having the vote at all that renders us ungovernable and the Union settlement untenable. Win or lose, this is our Bannockburn.

As Jim Sillars puts it, for 15 hours on the 18th of September in 2014, for the very first time in history, the people who live in Scotland will be sovereign as a matter of legal and psychological fact. And while it is quite possible that the relentless barrage of veiled threats and our own skewered self-belief will persuade us to hand our sovereignty back – and that decision will feel like a wholly negative one, a humiliating climb-down, a national failure of nerve that will feel, even to the vast majority of convinced no voters, like failure, it will nonetheless be our decision.

Our sovereignty will still be ours, our independence still in our own gift. Surely there is no one in Westminster or even in the Scottish Labour Party who imagines otherwise. The transfer of psychological sovereignty will be permanent, even if, on this occasion, we may decline it. The genie will not go back in the bottle.

A No vote, too, if it happens, will be no happy embrace of the spurious community of national families that good cop David Cameron ludicrously and insincerely evokes while bad cop Osborne quite sincerely threatens retribution. It is quite clear (on both sides the Tweed) that these men and all their tribe are in the thrall of a transnational movement to liberate the rich from all care for anyone else. And it will only become clearer and clearer over time that the only protection any community can have against that untaxable hegemony of those above the law is some form of sustainable, democratic collective political identity.

The UK, in the view of many of us, whatever else it is, is hardly that protective and inclusive community. Surely there is nobody even in deepest Surrey who believes anything like that anymore. Scotland, whatever its flaws and possible weakness and vulnerabilities, just might be.

Whatever else happens, then, a fundamental shift of sovereignty is under way in Scotland. It has a more cheerful face these days, and is made for the first time in my lifetime, of what feels like effective dreaming – of rich imagination and a real sense of possibility. All my ingrained cultural pessimism may be misguided. We may just do it. And do it this time against all expectations.

The breakup of what Tom Nairn called Ukania has been coming for a very long time. What is new to me is the feeling that at least a substantial minority of the people who live here in Scotland are living in something as Un-Scottish as hope, and that the very living core of that hope is a sense of self-governing, self-ruling, being sovereign over ourselves – not in some 19th Century costume drama way, but as modern, individual world citizens of every imaginable nest of complex identities – of gender and ethnicity – only one of which is the chosen pooled identity as civic Scots.

We are becoming sovereign over ourselves as individuals and can choose, if we wish, on the 18th of September, in those hours of political self-rule, to pool that sovereignty into a new identity with which to live in the real world. Whatever offers are made by the Westminster parties, they cannot offer us anything like that excitement, anything like that choice, anything like that protection. Sovereignty is something we can only create ourselves. And we are already creating it, it is everywhere, all around us. The referendum campaign, whatever its result will be, is only accelerating that irreversible tectonic shift. The UK as we have known it is exhausted and out of time. That is the reality with which everyone on these islands will shortly have to deal.

But remembering that I’m Scottish, I temperamentally have to anticipate a No vote in 2014, and point out that Bruce may have managed to repel an invasion, but he did not guarantee sovereignty at Bannockburn in 1314; to remind myself that it took until 1328 for the question to be settled in favour of there being two political sovereignties on the island of Great Britain. And then again, even 18 months ago, 2028 was an outside bet. Now I’d put my shirt on it.

From Global Dispatches - January 2014

“What matters most, I said, is what you are doing in England; what kind of country you want to make of the UK; and whether we in Scotland want to be part of it.”

David Donnison, Scottish Review 15th Jan 2014

David Donnison, Scottish Review 15th Jan 2014