“What matters most, I said, is what you are doing in England; what kind of country you want to make of the UK; and whether we in Scotland want to be part of it.”

David Donnison, Scottish Review 15th Jan 2014

David Donnison, Scottish Review 15th Jan 2014

Jim Sillars, one-time MP for Govan and Deputy Leader of the Scottish National Party, recently released a video talk on the upcoming Scottish Independence Referendum which he opens with a striking thought. On September the 18th this year, he says, between the hours of 7.30 am and 10 pm, for the first time in history, the Scottish people will be sovereign in their own country. They will hold their own future in their hands. They will have for those 15 hours, their independence. The choice before them, he argues, will be whether they want to give it back.

I hadn’t quite thought about it like that. There are a lot of things going on in Scotland (and indeed the UK) which haven’t really quite been thinkable before. The question before all of us over this next period of time, especially if we in Scotland vote No to Independence as the polls predict, is whether we’re willing to keep on thinking in new ways. Or if, on balance, we’d rather not.

The fact that there is going to be a referendum on Scottish Independence in September 2014 was not something anyone could have anticipated even four years ago when the Conservative/Liberal coalition took power in London in May 2010. The long term Labour administration the coalition replaced had facilitated the creation of an elected Scottish Parliament in 1997-9 with a proportional election system specifically designed to prevent any one party (the Scottish National Party in particular) from forming a majority government. To everyone’s surprise (including the SNP’s) in June 2011, the elections to that parliament did precisely what they had been designed not to do. A combination of the defeated exhaustion of the UK Labour Party and the transparent ineptitude of their Scottish C team (Labour in Scotland historically sends its talent South – Gordon Brown, Robin Cook and Alasdair Darling being recent examples) and of the visceral loathing for all things Tory within the Scottish electorate (out of 59 Scottish Members of the Westminster parliament, only one Tory is currently returned ) was enough to re-elect Alec Salmond’s A team (a minority administration since 2007) to a wafer thin overall majority – with their long term commitment to holding a referendum suddenly and unexpectedly upon them.

After some dithering in both Westminster and Edinburgh, David Cameron, the leader of a restive, sullen party in government , with at least one eye on the equally-to-be-avoided In/ Out referendum on British Membership of the EU, decided to call Alec Salmond’s bluff, and demanded a Yes/No question right now, if not sooner. A third option, that of an enhanced fiscal role for the devolved Scottish Administration with taxes being raised in Scotland for public expenditure in Scotland – which is what everyone in the political establishment up here secretly wanted and still actually expect – was taken off the plebiscitory table by an agreement between David Cameron and Alec Salmond for the conduct of the referendum under the constitutional aegis of the UK Parliament. What was arrived at was a long campaign towards a binary vote in September 2014.

The two traps the Prime Minister and First Minister had been set by the 19th century nationalism of their key supporters seemed suddenly to become manifest. The electorate in Scotland were caught too, with their favoured option not on the ballot paper. Indeed, having a ballot at all seems an imposition to many. With Scotland already well-established as a democratic political unit for the first time in its history, voters now find themselves being asked a question they weren’t expecting…at least not most of us and not yet. We had thought, all of us, I think, that the devolution compromise of 1997-9 which took place with administrations from the same political party being elected to run both administrations would be sustainable for a while even when both of those governments changed.

The whole business is being experienced as an irritating and unnecessary distraction from the tacit and incremental accumulation of powers by the Labour and Liberal parties in Scotland, who, despite having lost two elections in a row, regard themselves as Scotland’s natural government – much as the Tories do in London, even when not actually in power. We had a good thing going, they say, and the SNP and the Tories and the damn stupid electorate have conspired to disrupt a continuity which will be restored along with good sense in general once this ghastly business is over.

This proposition of a return to normality once we Vote No is still the received wisdom of the Scottish dinner party circuit. But I think that possibility of continuity is what is really being tested to destruction by the referendum campaign, no matter what the eventual result. It is becoming clear, I think, that change is not just irrevocable but that it’s not finished yet. The status quo may be on the ballot paper but it is not on the cards.

If any Scottish readers of this essay find one thing I say to take seriously, I would hope it would be that.

We have been tempted to believe in Scotland that our tactical pattern of voting one way in a Westminster elections and another in Holyrood elections would continue to shelter us from the worst neo-liberal excesses of Westminster – our parliament after all came into existence as a retroactive shelter from what was inflicted on us (and everyone else in non-Tory Britain) the last time the conservatives were in power. We are still behaving as if this is the case even while history is whisking that carpet from underneath our feet. This is just one of the ways in which it feels like we inhabit two versions of reality at once at the moment. It is unsettling partly because our political representation seems as terribly unequal to that reality as we are, and as far from any attempt at understanding it historically.

That reality of deep historical change doesn’t get close to being reflected in the day-to-day squabbling about the un-guessable minutiae of this or that future scenario that goes on between the tribal rivals of the Labour party in Scotland and the Scottish National Party. Part of the problem is that they are hard to tell apart – they both occupy almost exactly parallel consensual territory on the centre-left of politics, and their arguments often resemble the children’s game of “It’s my baw and ah’m no playing wi you”. But underneath the squabbling and insults and crystal ball gazing there is quite clearly an historical drift going on which appears to have only one direction. And it is this longer term and largely unarticulated movement towards the social, as well as national, fissuring of Britain, and how we manage or fail to manage that schism, that I would like to take this opportunity to attempt to articulate from a Scottish point of view.

We in Scotland suffer from the malaise of democracy as much as anyone else. We wonder, like everyone else, if it really makes a lot of difference who we vote for. We are sceptical, according to the polls, as to whether even the creation of a brand new country will really make a lot of difference. So, according to predictions in opinion polls (and in the confident expectation of the current UK government) we will probably hand our sovereignty and independence back at 10pm on September 18th this year and continue to think of UK elections as periodic swings between afflictions in whose make-up the Scottish Electorate (considered as such, as a unit) has no say. We will vote in these elections as British subjects, not as Scots, accepting therefore British governments, not as events we participate in, but as welcome or unwelcome gifts from elsewhere, from a place of power where these things are really decided. We will continue also to limit our trust in our Scottish elected representatives to their having merely a limited discretion on how we spend the tax we pay that Westminster then hypothecates back to us – the amount and extent of that to be based on whatever formula Westminster thinks fit.

That is the expectation. That all the speculation about whether or not an independent Scotland will be allowed to join (or remain) in the European Union, or NATO, all the futurology on both sides about how the negotiations would go on currency, on oil revenues, on fisheries, on control of the coastline with its enormous potential for wind and wave energy – will amount to nothing. That this period of consultation is really just a sideshow, that the devolution settlement of 1997 will be tinkered with, but that nothing will really change. Power will stay where it is, and we’ll like it or lump it, as the saying goes.

I now think that expectation is completely wrong. It is not that I am predicting a victory for the YES campaign in September…though stranger things have happened. It is rather that I interpret the fact of the referendum as historically symptomatic rather than as politically definitive. It is a headline, true…but it is a milestone along the way. And the direction of travel, is quite clearly towards schism…fissure…whether we want the change to happen or not. To my way of thinking, the big fact of separation of the historic nation of Scotland and the slightly less historic settlement of the UK is already testified to by the entirely different meanings that the referendum has for its two architects – David Cameron and Alec Salmond.

I am referring in part to the fact that the conducting of, and terms of this referendum were agreed to between the London and Edinburgh governments, and that both parties, I think thought they were agreeing to different things, and, were they inclined to be imaginative, would each find the other’s view of what they just agreed to incomprehensible.

Let me try to unpick that a little.

It is one of the many and terribly British contradictions of this story that the Edinburgh government has to ask the Westminster government in London for permission to have a referendum – and it is also terribly British that Mr Cameron said “Why, of course!” So far, so polite. But in the tradition of perfidious Albion…or of all politics everywhere, really, David Cameron was making a political calculation and proposing a political fix. Or that’s what he thought he was doing, on the basis of a version of reality in which The Scottish Problem, like the Irish Problem…is one of the white man’s burdens shouldered by Whitehall.

For Cameron, this was about tactics more than about history. It was quite clear to Westminster that electoral support for Independence in Scotland (whatever one might mean by such a 19th Century term in the 21st Century) is regularly testified to as an aspiration by around 30% of the electorate. This is too substantial to ignore, and not substantial enough to take seriously. It is also a figure impervious to election results, staying in the vicinity of that figure since at least the eighties. Cameron knew that Salmond knew the same polling data, and that the SNP leader was at that time arguing that a three question referendum – with an option to widen the powers of the Edinburgh parliament (to include taxation, energy and welfare, for example) – be put to the electorate. Salmond, in this way, being a politician too, was designing (or rigging) a referendum in a form that he knew that he could win it, in so far as a mandate for what we call Devo Max would have overwhelming political support and would continue the drift apart, the gradual separation of the polities. Cameron decided to call a halt to what he saw as Salmond’s game, and calculated that a Yes/No binary question was a political trap he could set for the SNP. Cameron would be, in effect, the Prime Minister who called Scotland’s bluff. The Scots would finally have to put up or shut up. (Or, as I have seen it expressed many times online – shit or get off the pot). He had no doubt at that time, that a No vote would be politically and historically decisive, putting the Sovereignty issue to bed, and radically reducing Scottish strategic leverage at Westminster as a bonus.

This is an expectation in which a very British complacency is as profoundly wrong as is the contrary , silent complacency upon which the Scottish wing of the No campaign is founded – that after a No vote we will carry on our leveraged incremental devolution as if nothing had happened. The London and Edinburgh wings of Better Together, are heading for victory and disappointment at the same time. If and when we in Scotland vote No, on the political surface, nothing may change. But like Wile E Coyote in the cartoons, who doesn’t start falling till he realizes where he is, historically speaking, we’re already over the cliff.

Politically speaking, I repeat, Cameron’s logic seems impeccable. Politically speaking, a No vote is expected not just to silence the Scottish question for a generation, but to settle the electoral hash of the SNP. The Scottish Problem, however, has both historical and political dimensions. So while the politicians are busy with the territoriality of political gamesmanship, history is quietly taking care of itself. This explains why the No campaign, Better Together, which is winning, always looks so miserable. While the Yes campaign, which is losing, looks so annoyingly cheerful all the time. Because the historical result of the political game is to make a question, or series of questions, about the future governance of this wee country that nobody was really asking, into the very present tense stuff of democratic political participation.

Perhaps it has simply been so long since the elites took democracy seriously that they have failed to anticipate what the exercise of popular sovereignty can do to political certainties. The independence referendum, squalid fix though it is, has suddenly opened up the democratic universe to something we thought had been lost when the Berlin Wall came down and an end was declared to it by Francis Fukuyama.

In short, History is back, and the future along with it.

(And they’re wrong too about the SNP’s electoral hash, by the way. A No vote in September 2014 absolutely guarantees an SNP victory in the next Scottish elections in 2016. Ironically, it may only be with independence that the political fortunes of centrist and centre-right politics in Scotland have any prospect of improving. If Scottish votes don’t count for much in the UK, then Tory and Liberal votes count for as little in Scotland. This is another side of our democratic deficit. There is much more of a middle class vote in Scotland than the miserable poll numbers achieved by the Tories would reasonably reflect, if middle -class voters in Scotland exercised the franchise out of individual self-interest rather than collective tactics – which is yet another indication that we in Scotland are not in “normal” territory according to the current consumerist paradigm of democratic choice. The paradox is that a distinctively Scottish right of centre party that allied itself in the UK parliament with the Westminster Tories would have much greater prospects of electoral success – along the lines of the Unionist parties in Northern Ireland. Indeed, historically, the Scottish Unionist Party (the old name for the Scottish Conservatives) did much better electorally before 1970 than the Scottish party merged into identity with the British Conservative Party has done since. I should add too that I’m using “middle class” in the European sense of “the bourgeoisie” rather than in the American sense of “just about everyone”.)

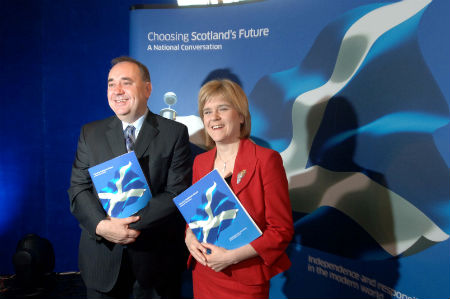

Scottish First Minister Alex Salmond and Deputy First Minister Nicola Sturgeon at the launch of the National Conversation 14 August 2007

The campaign for a No vote, Better Together, as it is called, is the creation of every electorally significant political party in opposition, and is supported by every major media outlet in Scotland, print and broadcast as well as every newspaper and broadcaster in London. Every department of the UK Civil Service is currently making a specific report on the advantages of Union, with a heavy, terrifying emphasis on just how difficult life would be, just how protracted and nasty negotiations on currency and EU membership would be likely to get should we be foolish enough to vote Yes. An Independent Scotland in 2016 as portrayed by Better Together looks an awful lot like North Korea, a bankrupt one party state and international pariah. They have also said some very silly things since. Ruth Davidson, the Tory leader in Scotland, notoriously threatened that if we vote Yes, we won’t be able to watch Dr Who.

(An insider from the campaign early on unfortunately bestowed the cognomen of Project Fear upon it. And he or she should have known better. Scottish public life is a very small, very leaky village. The Project Fear label was a gift to the Yes campaign, and Better Together are stuck with it).

Ironically, however, it is the universal nature of their support that is their biggest problem in terms of perception. The Scottish campaign is paintable as a lackey of a London master. Better Together are hampered too by the demonstrable fact that periodic changes of strategy (which may or may not pertain exclusively to Scotland) are decided on by all three Party headquarters in London, but the Liberal, Labour and Tory activists and parliamentarians up here don’t always seem to be on the list to get the memo. There have also been at least two occasions when Scottish Labour MPs and MSPs in particular have pre-empted UK party announcements in response to the very different political pressures they face in Scotland and blabbed on the telly about scrapping the Bedroom Tax, for example, before the London party was ready to announce that as policy.

Again, it is the Labour Party for whom the differential epistemology of Scottish and British politics is most difficult. They are faced with electoral pressure to move to the right in central and southern England, where UK elections are won and lost, against electoral pressure from the left in Scotland, where voters have been all too aware for a long time that votes in Scotland have scarcely any influence on the outcome of UK general elections. The Tories and the Liberals in Scotland aren’t subject to political pressure in Scotland at all, but only because they are to Scotland was Scotland is to Westminster – too small to be of any possible influence.

(There would be pressure on the Labour Party from the left in the North of England too, but those voters in safe Labour seats really don’t count any more than do the Tories and Liberals do in Scotland, or than the Scots do in Westminster. At least Scottish politics appears once in a blue moon on the political radar in London, rather in the manner of the village of Brigadoon, but with incomprehensible grievances rather than improbable song- and-dance numbers. It is the North of England that is arguably now the most politically disenfranchised area on the islands of the Atlantic Archipelago.)

Still, it has to be said that it is a tricky job for Better Together to sell the positive advantages of the status quo when the status quo currently includes a Tory-led government who are not only almost unrepresented in Scotland, but who are pursuing, even by their standards, a violently antagonistic set of social policies directed at those who weren’t fortunate enough to go the same schools that they did. Part of the test of these Tory Austerity years has been whether it has been possible for Scotland to shelter from the storm behind the walls of Holyrood. The SNP have had to claim to be doing their best while also saying that without independence it can’t be good enough. But the Labour opposition in Holyrood are also in the argumentative cleft stick of having to defend the institution their Party (albeit reluctantly) helped create, even when the wrong party, as far as they’re concerned, has somehow stolen it from them – the result being that each narrative cancels the other out, leaving us with history once again being much more interesting than politics.

(It is another of the entertaining paradoxes of all this is that although it was a Labour Government in Westminster who created, or rather, allowed the creation of, the new Scottish parliament, the Labour Party has never taken it very seriously, and is, partly in consequence, considerably weakened in Scotland by its very existence. Gatherings of Scottish Labour folk are punctuated by mutterings from an older generation saying: “A fucken tellt ye, dint ah?”)

This fissure of perception of what’s going on within the No campaign, only roughly identifiable as being between the Tories and their junior partners in the Labour and Liberal parties, has not yet emerged as decisive for the campaign’s fate, but it is crucial to the No campaign’s prospects. More importantly in the long term, it is testimony to a deep laziness of thinking about history, (or rather, of a failure to imagine the way that history is going) that determines that the same things, the same events, the same politics, cannot now help but have different meanings for us depending on where we live, and that this is as true of the Unionist project, as it is conceived in London and Edinburgh, as it is for out-and-out nationalists. The difference in meanings in all of these areas of understanding, cultural and historical, even within the political alliance of Better Together, is emblematic for me of what I now believe to be the UK’s systemic and historically irreversible dysfunction.

The No campaign, miles ahead in the polls, seems to be in constant nervous despair. Perhaps they intuit something of the above, or perhaps they just believe their own rhetoric, which tends to the “Nothing to be done” Beckettian end of political discourse. By contrast, the YES campaign, languishing in stubbornly unmoving polling data, seems paradoxically rather chirpy, as if aware that history, or something like history, is on their side. Not that their side is enormously distinguished by intellectual rigour either. Rather, their strategy is deliberately sweet and non-confrontational. They don’t hate anyone, especially the English. They don’t even hate the Labour party. They feel a bit sorry for them – which irritates the hell out of them. They are all about Hope!

(Scottish football supporters, with a well-founded reputation for aggression in the 1970s, hit on a very similar strategy in the 1980s. They became clowns, happy, red-wigged, tartan- costumed fun people who didn’t really care whether they won or not, as long as they could Hope. They loved everybody and everybody loved them. This not only helped a good deal with European police forces, it had the added bonus of pissing off the English football supporters whose propensity for violence is matched only by their constant bewildered outrage that the English football team doesn’t win everything all the time. )

What is now emerging, in politics as in football, is that amiability and optimism are now themselves the crucial issues of the campaign. In contrast to Better Together, the key argument of the Yes side is that once the Scottish people take the simple step on September 18th of voting in the existentially affirmative, it will then be in the interests of not just the Scots, but of the EU and NATO and the UN and the IMF and even of what they charmingly dub the” rUK” (r being for “rest of”, or “rump”) to maintain smiling, optimistic amiability. How would it serve the EU to make life difficult for a country whose coastline abuts all that oil and all of those fish? they argue. How would it serve the rUK to disrupt its own economy by playing hard ball with the country where all that good whisky comes from? Independence, they insist, doesn’t mean that we’re going anywhere. It doesn’t mean we can’t be friends. Can’t we be rational about this? You can still come and stay for your holidays.

(Yes, divorce settlement as well as football metaphors abound hereabouts.)

Since we’re talking about history as well as politics, historians can point out that countries don’t always act in their own self-interest, particularly when it comes to the neighbours. They can point to the specific history of Scotland and its larger, much more populous cohabitant of these isles, and reflect that between William the Conqueror in 1066 and George II in 1746, every King of England but two sent an army North or fought and defeated an army coming South…and that an awful lot of time was spent by Scottish monarchs and their families as willing or unwilling guests in some English fortress or other. Scottish sovereignty has always been partially dependent on whether or not we could count on the English being away fighting somebody else.

In modern times this last consideration is matched, perhaps, by the situation between the UK and Europe and the possible referendum on UK membership of the EU, which is, in contrast to the Scottish affair, a referendum that David Cameron takes terribly, terribly seriously. He has been forced to do so by political pressure (like Labour, from his right, within and without the Tory Party) to concede an In/Out vote should the Tories form a majority UK government after the general election in 2015. The fact that this might result in a vote in England that by sheer numerical disproportion (roughly eleven to one) takes a Scotland that has just declined independence from the UK out of the EU, against the wishes of the Scottish electorate, is an irony hard to overlook. If UKIP (the UK Independence Party) really do top the polls in the European elections this year it will be a sign that dysfunction runs very deep indeed in these islands, and that English National Feeling, which is what the vague anti-immigrant atavists of UKIP represent, is as potentially disruptive of the polity, in its primitive, xenophobic way, as is the much slicker, more honed, immigration-friendly civic nationalism of the SNP.

Better Together partners (from left): Johann Lamont, Alistair Darling, Ruth Davidson and Willie Rennie

This scenario is already an occasionally offered titbit by Nicola Sturgeon, who is the effective day-to-day leader of the Yes campaign for the SNP, and who is proving herself to be a formidable political operator in her own right, recently destroying the newly appointed Secretary of State for Scotland, Alasdair Carmichael in a head-to-head on STV. Carmichael, who was brought in from the UK parliament as a political tough guy, was reduced to asking the TV moderator of the debate to “make her stop”. More school yard echoes in Scottish politics aside, the SNP no longer has to rely so heavily on Alec Salmond’s slippery charisma.

(There was something of Ali and Foreman about the encounter between Sturgeon and Carmichael…two versions of Scottishness, like two versions of black America…then there was Nicola Sturgeon’s aesthetic decision not to punch her man as he was on his way down…but I digress.)

All of this, history and politics aside, comes down eventually to how we think about where we live, and whether or not we think that Scotland can emerge as a functioning entity. It is also a question as to whether we think the UK can ever escape from its own democratic dysfunction. We in Scotland have more or less given up on changing it just by voting in its elections. We haven’t voted for anyone but the Labour party since World War Two (except once, just, in 1951) and it hasn’t made any difference. Worse, when the rest of the country voted with us in 1997, we got New Labour instead of what we thought we’d been voting for all this time. So, we might conclude, the best way to change Britain, or to get it to change itself, is to break it.

Anyway, in or out of the Union, whether or not we believe in democracy any more, our distinct identity as Scottish is not in question and is not really much of an issue in this campaign. The bright and chirpy Yes supporters seem, if anything, rather less Scottish culturally than the doom struck cringers of Better Together. This, I think is enough to answer the question that most irritates the Yes camp, that what is happening right now in Scotland has got nothing to do with Mel Gibson’s ludicrous and genuinely Anglophobic movie about William Wallace, Braveheart, where the portrayal of the Scots had more to do with shop-worn, Rousseau-esque fantasies about noble savages than it had to do with any attempt at…well…research.

Back in real history, the 1707 Treaty of Union between the London and Edinburgh legislatures always acknowledged a distinct Scottish identity, and specifically excluded Law, Education and Religion from amalgamation. (The settlement was a little less generous about the Gaels, whose status was roughly that of the Aborigines when the Scots and English and Welsh and Irish turned up together in Australia). Structurally, the deal was a partial, unequal and grudging one. There were a series of ineffectual riots at the time. There can be no question, though, that Scottish people played a full and enthusiastic part in the creation and management of the London-centred British Empire and shared in the financial and trading wealth of the Empire. Jocks are everywhere too in the trading hub that London remains.

(To pre-empt and pre-locate my later assertions a little, “London”- the world trade centre, as opposed to London – the place where most Londoners live, is the only real successor to “Britain” considered as an enterprise.)

Scottish identity within Britishness in any sense has never seriously been challenged or even questioned. But we participated in the spoils of the world as North Britons as well as Scots – as Britons in Scottish costume, or as Scots with British backing. It’s never been a simple matter. Even Bonnie Prince Charlie, cockaded in Highland Regalia and celebrated in sentimental song, wasn’t interested in Scotland as such. It was Britain he was after. And it was the Unionist Walter Scott, whose statue is still everywhere even if his novels largely gather dust, who was the individual most responsible for codifying, even for inventing Scottishness as we now think of it culturally. There is a coherent case that it was Scott’s forging of collective memory in historical fiction, and his deliberate fusion of elements of Gaelic culture (in clothing and music) with the English speaking Lowland culture of which he was the bastion, that is responsible for there being such a place as Scotland at all – that Scottish identity itself is a Unionist project.

(I said that once to Nicola Sturgeon in a BBC radio discussion, years ago. She looked at me like I’d grown an extra head.)

The imperial project – in which Scots financiers and Scots soldiers in kilts led by bagpipers were such enthusiastic participants – notoriously reached its zenith in 1914. The story of the hundred years since that now apparently-to-be-celebrated anniversary has been that of the break-up of that Empire, and by extension, of “Britain” itself. Without an Empire, the argument runs, the idea of Britain is incoherent. And now that Protecting Protestantism from the Pope is no longer a key issue, all that’s really left holding the Union together is the sense of threat to existing social privilege.

This was argued first and best by Tom Nairn back in the seventies, when Scottishness or the “Scottish problem” re-emerged as a factor in British politics. Nairn argued that the then situations in Wales, of the burning of holiday cottages and moves toward linguistic and cultural assertion; in the Scotland of the electoral decline of the Scottish Unionist Party after it was disastrously assimilated into the UK Tories and of the rise of the SNP; and the then Civil War in Northern Ireland, were all symptomatic of a project of Union that had run out of logic as well as steam.

The decline of Tory representation in Scotland became precipitate later under Margaret Thatcher. If there is one person to be identified as making an unhealable wound in the Union, it is probably her.

Nairn’s book “The Break Up of Britain” remains for many the seminal text of modern Scots Nationalism. I would argue that its central tenet – that the revived sense of Scottish nationhood is consequent upon a decline of a sense of Britishness was not necessarily tenable then, but that since the election of Margaret Thatcher in 1979, and the consequent revolution in the economic and social direction of the UK nation state – what Nairn called Ukania – his case has become pretty much incontrovertible. Constitutional change now seems inevitable, if not imminent, because deeper, cultural change in all of these Atlantic Isles now feels tectonic, beyond volition.

I don’t claim any special insight. This sense of inexorable and unintended drift is as much a matter of feeling as observation. Everything does feel different in Scotland, even from the time of the last referendum in 1997 and the quiet, almost bored decision to set up the devolved parliament in the first place. It feels different, in a rather scarier and less positive way, in much of England too. I can’t speak for Wales or Ireland – I’ve not been for a while – but I bet it’s true. And while I’m indulging in overt subjectivity, let me identify this feeling of dislocation as becoming clear to me before the current hoo-ha. The 2010 UK election, though I was under no illusion as to its importance, felt to me, despite my wish to engage in the event, as if it were happening in someone else’s country.

The Scots have felt for some time a push as well as a pull when it comes to the idea of Britishness. Indeed, I would argue that the newly-felt distinctiveness of the political culture of Scotland really hasn’t got that much to do with a positive, willed movement for change, let alone a will for “leaving” anyone. What I can identify with certainty is the equal and opposite feeling – the feeling that we are not so much leaving as we are being left.

This feeling, along with the other feelings, are not, I concede, evidence. But part of what we are discussing here is national feeling. And on the topic of feeling, I would add to Nairn’s core analysis that the key moment, perhaps the first moment, of a true, modern, democratic, communal, inclusive, popular “feeling of Britishness” was in the coming to power of the Labour government in 1945 – at the moment of victory in World War ll. Modern Britishness was inherited from that communal moment and continued as a project by succeeding UK governments on the basis of what we now call the post-war consensus. The key element of this consensus was that the economic priority of government was the maintenance of full employment –and cascading from that priority came policies of social and regional inclusion – then extended in the sixties in matters of gender and sexual orientation. We were all in it together in the Second World War, so we were all in it together now. In political terms, the wartime coalition of an eccentric, brilliant, imperialist to run the war and foreign affairs, and a bluff hard- nosed trade unionist to run war production and the domestic economy was to be, in softer, murkier form, continued, more or less, through the social reforms and industrial strategy of the fifties and sixties.

Although this political and economic consensus came to grief in the seventies and eighties, starting with industry and employment, the values of the post-war consensus are still pretty much where most people in Britain sit, politically. It is among the political elite, sitting in Westminster, the New Labour Party very much included, that such values seem hopelessly antique, and useful only as a marketing device. A new elite consensus has emerged in Britain as well was everywhere else. This global elite consensus would have it that the value of “freedom” is now equivalent to individual consumer choice through markets, as opposed to being invested in the collective exercise of self-determination. Nationalism, like socialism, is so twentieth century.

In opposition to this new elite consensus, in Wales there is Plaid Cymru, and in England, for the moment, barring a rediscovery of populist mojo by Ed Milliband, there is UKIP. In Scotland, however, we have a progressive, broadly left wing and socially liberal alternative to New Labour when it comes to expressing these British values electorally. Ironically, they’re called the SNP. The Scottish Labour Party still try to identify themselves with the “old” values of 1945 – indeed, that is the attempted emotional appeal of a campaign called “Better Together.” Unfortunately for them, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown’s “New Labour” Party specifically and convincingly abjured the Party’s historic identification with the “socialist” values of 1945 back in the 1990s, as (they thought) the price of electability in the UK. It may be, in the years to come, that the rather less developed English Nationalism of UKIP which also seems to yearn for a time of inclusion and the valuing of people beyond the marketplace, provided they are the right kind of people, will one day evolve beyond considerations of ethnicity and arrive at a more civic sense of belonging. The SNP had some pretty unpleasant roots of its own in the twenties and thirties it had to deal with, after all, before they re-invented themselves, convincingly or not, not so much on the model of Old Labour (they have no Trade Union affiliations, officially) as on that of the European centre left.

In any case, it is surely no accident that the re-emergence in Britain of nationalist feeling in the Celtic satellite nations coincided exactly not just with the decline of Empire, but also with the collapse of the international as well as national post-war consensus on the use of mixed economies to attempt to combine freedom with equity. It is clear now that the moment in 1973 when the oil crisis precipitated the international upheaval that changed the elite’s ideological direction of travel away from nationally managed welfarism towards a market and credit-led transnationalism, and then to what we came to call globalisation, was at the very least historically coincident with the moment of the sundering of the national, as well as the social, fabric of Britain.

Everywhere in the world since that great change, the global and the local have had to be re-negotiated. A whole new set of tensions have been wound up with identical origins but in divergent localities and in forms as varied as, say, Salafist Islamism or Chinese State capitalism or the rise of the Catalan nationalists in Barcelona or of the SNP. Everyone is reacting to the same thing at the same time in different ways.

Specifically, we in Scotland are reacting in our own specific way to our most local manifestation of globalisation. This is the alienation of London, as a world city and trading hub, from the rest of these islands even as it concentrates more and more wealth and power from the globalised elite. The key historical fact of Britain in the 21st century is the Undeclared Independence of the London City –State. Already living in an economy entirely divorced from the rest of the islands, the current London branch of that international elite, as represented by Tony Blair as much as by David Cameron , are understandably impatient with what they experience as the baggage of welfarism and the tedium of their outworn “obligations” to the anachronism of the “nation”.

(This universe, I hasten to add, is not really geographically specific. Hackney and Camberwell , other than the nice parts, have as little to do with elite London as do Grimsby, Aberystwyth, Port Rush or Cumbernauld.)

Those who sit now at the centre of the universe of wealth and power (where David Cameron was born and Tony Blair has scratched his way in), though cities like London are where the river of their money flows, are themselves less than ever geographically located. They own the nice bits of everywhere. They go for lovely holidays in the poorest countries in the world, as well as shooting and fishing by the banks of the Spey. They are uncomprehending, therefore, of any kind of nationalism. It seems prehistoric to them, atavistic, childish. In Scotland, they appear to really think it has something to do with face paint and football jumpers. In fact the nationalism they so despise in the Scots, perhaps surprisingly in people who drape themselves continually in the Union flag, is very much what they despise in “Britain” too.

Our local elite have set out, avowedly, to destroy everything that Britishness has historically meant as a shared, collective, positive, popular good. They are perhaps doing this unconsciously, as they have never really shared anything. Britain as a place of shared memory and human value never meant that much to them, just as all that Empire and flag- waving stuff, as George Orwell pointed out, was never interesting to anyone BUT them. In summary, when David Cameron says the word “Britain”, he doesn’t mean the same thing as most people in Britain do, no matter which side of which border we sit on.

The British ruling class which he represents is every bit as much an insular village as Scottish public life. And they don’t see what the problem is. I don’t expect they ever will. But this ruling class is the deeply distorting dysfunction at the heart of why Britain doesn’t feel like it works anymore. It was this British ruling class, too, that the Scots ruling class decided to join in 1707, and for whom the local colour of their Scottishness was, and remains, a social cachet. It is the coat-tails of this British Ruling Class whose hegemony is that to which the Unionist side in the referendum debate would have us continue to cling, even as the British Ruling class themselves become less and less identifiable as such, as the international super- rich themselves homogenize, and as an internationalised, flattened and expressionless form of English becomes the modern equivalent of medieval Latin.

I would argue that what heat and anger there is in the Scottish referendum argument comes not from any Celtic resurgence, but rather from the recognition that the values we used to call British are under threat not from people with Saltires painted on their faces, but from people with Union Jacks on their waistcoats. And that therefore, even in the absence of a decisive Yes vote, from the point of view of all the people in these islands who still share any values of democracy or social justice, the best thing the Scots can do on September the 18th is to vote YES in sufficient numbers to give the bastards a fright.

(Why use such crude, emotive language as “bastards”? Is this what Scottish barbarians are like below all their talk of consensus and amiable negotiation?)

In modern times, Scottishness, rudeness included, has been a political strategy – the threat of disruption used to extract social and democratic concessions from Westminster. It may well be, however, that the calling of this referendum, superficially consistent with that paradigm, in fact marks a paradigm shift. We may be moving into new territory. To put that in practical terms, those of my friends who plan to vote No because they think that a No vote represents a vote for a status quo in which Scotland has done rather better than regional England, and that this situation will continue, are certainly being optimists and are quite possibly deceiving themselves. If we vote No decisively, I don’t think the neighbours will fall for it any more. We may be forced towards adulthood whether or not we want to leave the house. Despite ourselves we may have to become ourselves.

Since 1999 and the forming (or re-forming) of a parliament in Edinburgh, the Scottish electorate have regularly been asked to think about some aspects of government, but not all. UK-wide elections, in which we take part as British Citizens voting for local representatives to be sent to the legislature in Westminster, is where the grown-ups take care of what used to be called “the commanding heights” – economy, taxation, defence. The Scottish Parliament only oversees what used to be the unique purview of the Secretary of State for Scotland, a member of the British cabinet responsible for guiding the decisions of the UK government through the already, and always, distinct institutions of governance in Scotland. In strict constitutional terms therefore, Scotland is no more “sovereign” now, as a polity, than it was in 1997 before the referendum that established a devolved parliament to oversee these areas.

What has changed since then, is much more numinous, much more located in sense and feeling than in constitutional clauses. This just feels like a different country now. It is obvious in Scotland, but I think it’s true in England, and especially in London, too.

Most importantly for me, Scotland does not feel like the same place it was when I was the same age as my children are now. It feels better, stronger and more confident, despite the recession, despite austerity. And it is also now a place where people from around the world want to come to live and work. Thirty years ago, when I came back up here because I had failed to find a niche in London, it was a place for energetic, ambitious people to leave. Coming home felt like failure then. Not anymore. It may even be, we are just beginning to dare to believe, that re-inventing ourselves may not be quite the impossibility we’ve always assumed. It may even be an opportunity. We may even be allowed to hope. We may not have to ask permission anymore.

So, to sum up, home is beginning to mean very different things to different people on these islands. To the ruling elite, home now is as much in New York or Davos as it is in the town house in Hampstead or the country house in Chipping Camden. What nationalism in the 21st century might mean, in Istanbul or Budapest as well as Edinburgh, is the assertion of localised alternative values to those of the global marketplace and its associated, globalised wealth; that even though we don’t live in that lovely, distant world of privilege, we are still of value.

But of value as what? As humans? As Muslims? Well, as Scots for example…some of whom are Muslims and all of whom are humans. How about that? Civically defined, of course. We’re modern too, you know. No, this is 21st century civic nationalism. Anyone who lives in Scotland gets to vote, no matter where they were born. And we won’t be sending any ballot papers out to the Caledonian Diaspora in Winnipeg or Adelaide. Or Chipping Camden.

Identity, as Amin Malouf has written so eloquently about Lebanon, isn’t what it used to be. In a trans-national world one may define freedom itself, not as Mel Gibson did, with blue face paint and a kilt, as some form of essentialism, but as a constant negotiation and renegotiation of brother and sisterhoods to which we happen to belong at different times and under different circumstances. Malouf is an Arab who also happens to be Lebanese, and Christian, and Protestant and who happens to speak French and to write books for a living…and hence he has a choice of fellowships to belong to. He identifies the moment when someone insists that you have only one identity as the very moment of oppression, whether they are shooting you for it or handing you a rifle and demanding that you shoot someone else.

The referendum, like the rest of politics in Scotland, is still perhaps a matter of strategic calculation more than of conviction. Like the rest of the world, perhaps, we are skipping between our multiple identities as suits the needs of the moment. But we are also privileged, in this moment, to be taking part in history as well as watching or feeling it. We should combat the occasional darkness which comes over us as we contemplate the possibly dire results of our decision going either way and reflect, like Jim Sillars did, on the meaning of having this decision at all. At being sovereign, as we will be, between the hours of 7.30 am and 10 pm on September the I8th this year.

Maybe we should sit back before deciding whether 15-and-a-half hours of sovereignty are enough and reflect that the very fact that this event will carry such different meanings and weight across our borders and within them indicates that the tectonic plates below our feet never have and never will cease to move.

And if Walter Scott as a British Unionist could write novels about Scotland and its heroes that were then held up to be models of small country nationalism in the 19th Century, quite contrary to his intended meaning, then perhaps in the 21st Century we should embrace contradiction and complexity also, and perhaps ask observers from elsewhere (like Quebec or Catalonia) to appreciate the nuances and contradictions of our particular debate as we learn to appreciate theirs, in a spirit of difference as well as fellowship.

We are being asked a digital question, but are living, like the Quebecois and Catalans and everyone else, in an analog world. Perhaps we can be an example to our fellow humans, if, along the way, we can ask ourselves some more complicated and interesting questions about local and global citizenship before we make the rather dull decision we’re being asked to make between shutting up or fucking off.

My serious point is that in this moment, our asking ourselves these questions can change the world, as well as describe it. Even it is only this wee corner of it.

The YES campaign has already succeeded in opening an imagined civic space, largely online it must be said, for thinking what might be possible for us in our little northern corner of Europe, should we choose to assert ourselves as ourselves. That sense of possibility and hope, I think, is something to treasure and hold onto if we can. It is also something apart from oil and whisky that we can aspire to export.

Polling data suggests that the No vote is strongest among the best-off Scots, suggesting that the Union itself is an expression of class interest. Ironically, however, it is the establishment nature of their support that is their biggest problem in terms of perception. If, as seems more likely, we vote No, and so decide to hand our sovereignty back , and forgo the temptations of Hope, then we will have to work very hard together to ensure that a legacy of bitterness and failure does not last for years. The Labour Party in particular will have to come through with a transformative narrative if they are not to be judged forever as the minions of a foreign and quite possibly hostile power. Just as we may come to regret electing to remain a part of a United Kingdom which took us to war under New Labour and out of Europe under the Tories.

But then, having done this democracy business once, we can always do it again. Sovereignty might get to be a habit, just as voting in Scotland for a national parliament in Scotland, however circumscribed, has, unheralded and largely unremarked, already transformed our sense of ourselves and what it is possible for us to become.

No comments:

Post a Comment